BOOK: The Peasants of Ottobeuren (Govind Sreenivasan)

Precis

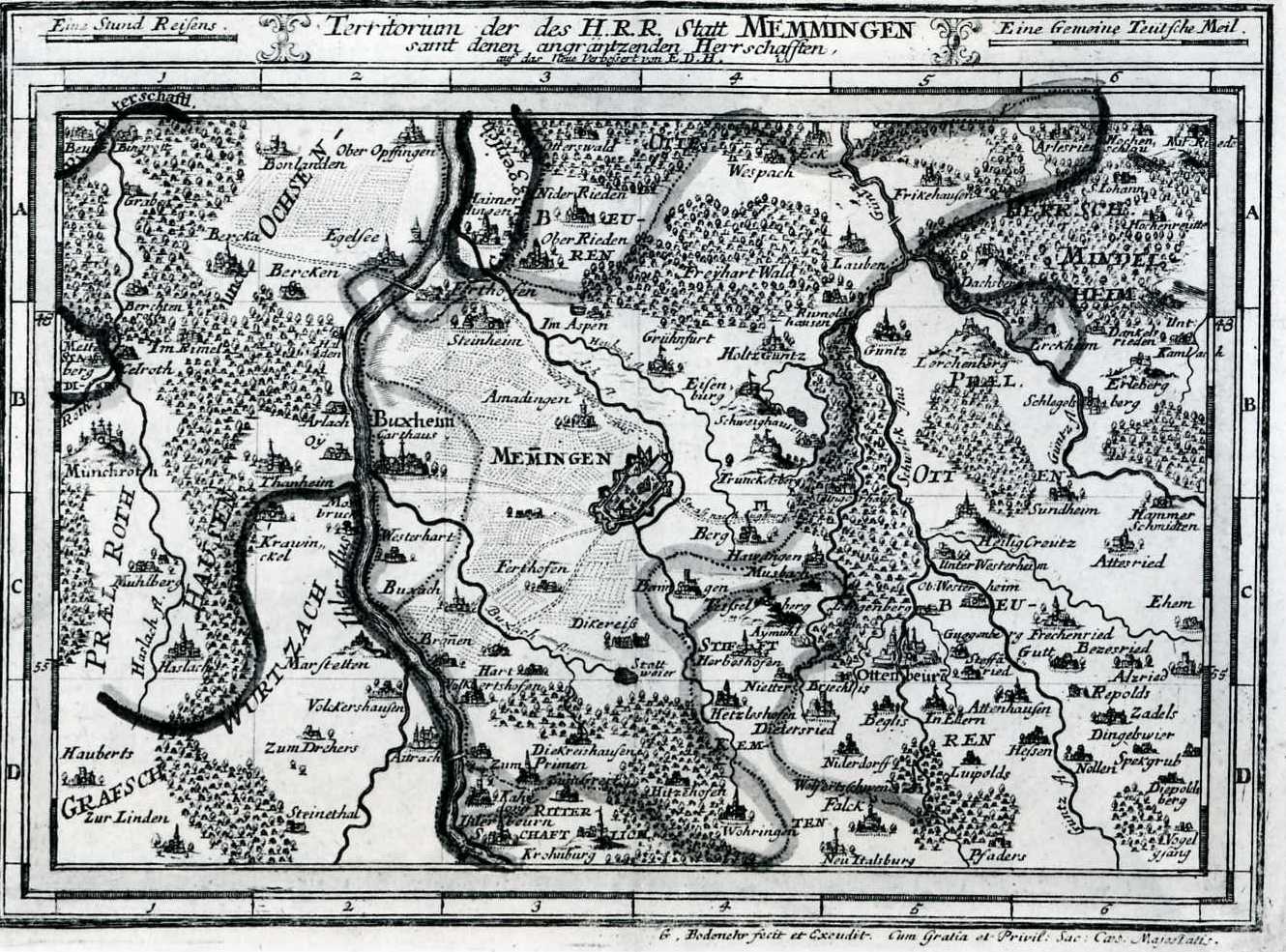

The Peasants of Ottobeuren is, in the words of its author, a revisitation of the old debate over the "transition to capitalism" in light of what he sees as the unmoored structure of early modern European social/economic history given the unfashionability of such grand narratives (p. 6). The author takes as his case study the lands of the Benedictine monastery of Ottobeuren in Upper Swabia, modern Bavaria (near the city of Memmingen, seen in the top-center and right in the picture above). The central argument goes something like this:

- By the early 16th century, the Ottobeuren peasantry had won for itself secure, de facto hereditary tenure and relatively light seigneurial extractions (pp. 19-27; pp. 131-137). Peasants routinely subdivided their holdings, legally or illegally (!), to pass on to their children as inheritance. Peasant society was divided between well-off Bauern on larger holdings (Höfe) and poor Seldner who lacked adequate holdings and therefore subsisted on alms, paid labor for Bauer neighbors, animal husbandry, etc. Cash was relatively scarce, barter was common, and markets were highly regulated and compartmentalized (pp. 94-105).

- Over the course of the 16th century, the population grew while peasant subdivision proceeded apace. Contra the Malthusian model, the Ottobeuren lands continued to produce grain surpluses (pp. 123-131); nevertheless, a distributional problem existed as continuous subdivision threatened to create more and more households with economically unviable holdings (pp. 145-154). Recognizing the issue, in the latter half of the century the Bauer village elite collaborated with the Abbot to "freeze" the number of households by introducing impartible inheritance.

- Impartible inheritance required prospective heirs to buy out their parents (and siblings) in order to acquire property. Parents would then retire on the funds (paid out in installments), while "yielding" heirs would get lump sums and make their living as servants until they could marry into a new family unit (and purchase its holdings, if possible). In order to finance such acquisitions, peasants usually needed recourse to credit (pp. 176-194). This dramatically increased the need for cash in the peasant economy, resulting in more widespread commercialization (and specialization) as peasants began to produce more for the market (pp. 263-279). The compartmentalization of the late medieval market increasingly broke down under the pressure of widespread smuggling (pp. 335-337).

In short, Sreenivasan identifies a "transition to capitalism" in Upper Swabia that conforms to neither the Brenner model of class struggle-cum-dispossession, nor to the model of urban dissolution of rural barriers to trade. Along the way we learn some interesting things about the Peasants' War, the various divisions within peasant society, gender and kinship roles, and so on.

Comments

First, it should be said that the book is not only very sharp and well-argued, it is also eminently readable.

Despite his reluctance to use the term himself (pp. 348-349), I think Sreenivasan convincingly demonstrates that by the early 18th century Ottobeuren developed into something that can be justly called agrarian capitalism (insofar as households are dependent on monetized, relatively open markets for inputs and outputs, and routinely reinvest their surpluses into their business operations). He does so in a way that beats the dead Brenner horse further, which is always fun.

The question remains what significance this transformation had. Again contrary to the old Marxist narrative, this transformation does not seem to have unleashed modern economic growth (p. 344-345; although Sreenivasan plausibly posits it was a prerequisite for such growth), nor does it seem to have precipitated political modernization (as he notes on p. 37, "the structure of late medieval Swabian lordship proved to be rather more durable than some historians would like, remaining unchanged in its essentials from the close of the fifteenth century to the Napoleonic era."). There is no question that it fundamentally changed household reproduction and relations within the kin group, but nevertheless we are left a decidedly deflated concept of capitalism, one whose development is no longer the lynchpin of a world-historical narrative of modernization. This is a more defensible concept, so this is not a criticism; but it does mean it loses some of its analytical appeal (not to mention its political salience).

Quotes

How did engagements come into dispute? In some cases it is hard to believe that there was any real promise of marriage, and it seems more likely that the lawsuit was an effort to redeem a moment of unguarded passion. Thus, when Magdalena Fuchsschwantz of Fredchenrieden alleged that Balthas Fischer of Ottobeuren told her "I want to screw and to shit, and by God I must have you!", or when Barbara Lutz of Attenhausen claimed that Jerg Meschlen said "Let me into your house! If I can't have you my ass will burst!", the modern reader is hard-pressed not to wince at the court clerk's continuation "... which words she understood as a marriage proposal (p. 249)

The object of market ordinances was thus to guarantee that the needs of the local community would be met affordably. There was no desire to bar outright either the export of goods or the flucuation of prices, which were understood to reflect - and properly so - the interplay of supply and demand. It was, however, a firmly held conviction that the ability of the individual settlement and of the monastery lands as a whole to support themselves should not be compromised by the demands of outsiders. As for prices, it was felt that the only fair determination of the balance of supply and demand emerged from the face-to-face encounter of producer and consumer … Justice in exchange, in other words, was best achieved through temporally instantaneous transactions which gave precedence to the needs of the spatially immediate. These conditions were most likely to be realized, it was felt, when exchange was confined to officially sanctioned times and places. (p. 97)

Thus far, our investigations of the health of the rural economy at Ottobeuren has produced a set of distressingly incongruous results. There is no gainsaying the unspectacular level of agricultural productivity in this period. That a long wave of population growth came to a decisive halt in the last third of the sixteenth century is similarly undeniable. At the same time, however, it seems clear that the demographic system was not regulated by mortality. There is unequivocal evidence of a substantial and even slowly growing agricultural surplus. Finally, the increase in the monastery's exactions was borne manageably (if not cheerfully) by its subjects. It is hard, in other words, to discern the traditional production crisis amidst this evidence, but it is equally hard to avoid the conclusion that some kind of structural constraint had come into play.

For a clearer understanding of the nature of this constraint, we need to take a closer look at the process of agricultural production. What we will find is that even if the monastery lands as a whole produced an agricultural surplus, this was not true of the majority of individual households (p. 145)

It may seem unnecessary to insist on (perhaps to belabor) this latter point [ed: that by 1600 "householding in Ottobeuren was characterized by a constant preoccupation with questions of cost, investment, and yield"], but the time-honored contrary view, according to which the logic of the peasant family economy is diametrically opposed to the logic of a capitalist economy, remains extremely tenacious. I do not mean to suggest that the Abbot's tenant farms were run no differently from an Antwerp trading concern or a Manchester cotton mill. At the same time it is immeasurably further off the mark to view the Ottobeuren household as an organic unity where, in Weber's famous characterization, the members worked to the best of their ability, consumed on the basis of their needs, and no accounts were kept among kin." (pp.263-264)